Search our articles

Another view of China’s deep involvement in global supply chains

Key Insights:

- What is happening: Rhetoric on the derisking of trade from China has been growing steadily, driven by rising geopolitical tensions. Yet, trade complementarity between China and these major trading partners is still strong.

- Why it matters: Derisking may not meaningfully reduce a firm’s exposure to China-related geopolitical tensions as it is difficult to extricate China from global supply chains.

- What happens next: As US import needs are still aligned with what China exports, Chinese inputs, intermediates, and final goods will likely continue to find their way into the US market through other countries’ manufacturing supply chains. China will double down on its push for self-reliance, as trade complementarity data shows some initial success.

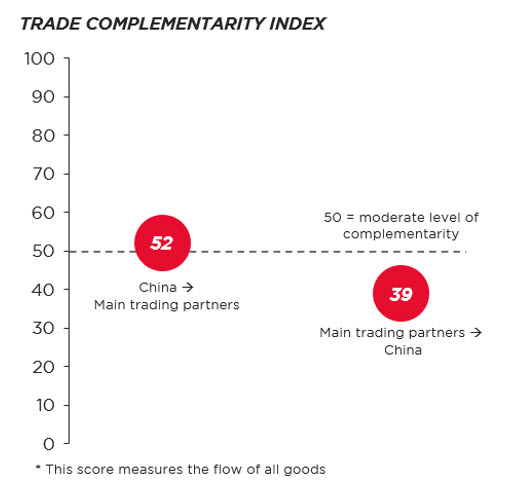

Rhetoric on derisking of trade from China has been steadily growing in the past few years as geopolitical tensions between the EU, US, and China mount. Yet, this rhetoric belies strong trade complementarity between China and these key trading partners. In particular, the trade complementarity index (TCI) tells us, at a high level, if country A exports what country B needs, and vice versa. The index is scored from 0 to 100, with 50 as a midway point indicating a moderate level of complementarity.[1]

China's role in global trade is increasingly controversial as the country seeks to export to the world as its main growth engine. Between 2019 and 2023, the value of China’s exports grew 35% while China’s political leadership strives for domestic substitution in strategic industries. Beijing appears to have some early success in pushing for self-reliance and greater exports. The TCI score for goods that China’s major trading partners export to the country is 39, below the midway point of 50. In contrast, the TCI score for China’s export to its major trading partners is higher at 52. In other words, China’s main trading partners needs a broader variety of the type of goods it exports than China needs from them – a reality that has been uncomfortable for trading partners who seek reciprocity.

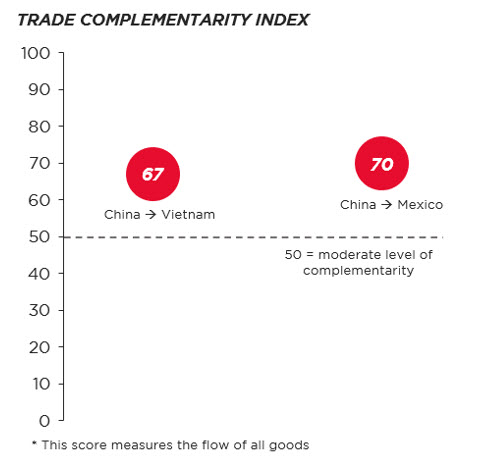

If we narrow down to Vietnam and Mexico, two key derisking countries, we find that China’s export profiles are still largely aligned with their import needs. This aligns with other data suggesting a high degree of Chinese content in Mexico and Vietnam’s exports. In 2020, China’s value add in Vietnam’s exports was 15% of global value add, a 6 percentage points increase from a decade earlier. Mexico saw a similar increase of 3 percentage points. Therefore, even when firms relocate to other production locations, they may not be meaningfully reducing their China exposure given the high degree of China content in these countries’ manufactures. Onyx has touched upon the deep positioning of China in global supply chains in our 2024 midyear outlook and a previous study on the internationalization of Chinese firms.

More critically, the US and China are still highly aligned on their import and export profiles, despite trade tensions over the past decade. Across all product lines, China’s exports to the US recorded a TCI score of 69. This high level of complementarity is also bidirectional; US exports to China had a TCI score of 70. Both countries have been trying to find alternative trade partners. The US has turned primarily to Southeast Asia and Mexico for these imports, while China has looked to Japan, Korea, the EU, and emerging markets for a mix of high tech and agricultural goods. Yet, China’s persistent need for American proprietary technology in high value-added goods will continue to be a political pain point for Beijing that Washington seeks to leverage.

[1] The dataset used here is World Bank’s calculations of a given country’s TCI score across all goods. The World Bank TCI is scored from 0 to 100. Other TCIs are usually calculated at the product level and/or scored from 0 to 1.

Topics: Asia, Southeast Asia, North America, Trade, Nearshoring

Written by Onyx Strategic Insights